By Imogen Rattle and Alice Owen

Carbon intensive industry is concentrated in particular areas, but UK industrial decarbonisation policy is centrally controlled and funded. A national framework is needed, but what routes are there for local action to ensure the low carbon transition doesn’t leave some places behind?

Wind turbines, electric vehicles, thermal insulation – the low carbon transition relies upon industrial materials. But the activity that creates these materials is also a major contributor to climate change. In 2020, energy-intensive industries such as steel and iron, cement and lime, chemicals, paper and pulp, ceramics, glass and oil refining, accounted for 26% of global CO2 emissions. These heavy industries are considered particularly “hard to abate”. Plant costs are high and require an investment case to upgrade, while long facility lifespans weaken the argument for upgrading before an asset becomes uneconomic.

Carbon capture and storage (CCS) and switching to fuels like low carbon electricity or hydrogen will be key technologies to decarbonise the sector but many of the solutions are at a low level of maturity and will require time and investment to realise their contribution. In the interim, energy-intensive industries need to focus on innovations in material and energy efficiency, but narrow profit margins and the lack of a ready market for low carbon materials provide limited incentive for them to invest this work. To decarbonise industry at the required pace, government support is needed to set standards, plan and develop infrastructure, and support innovation.

In 2021, the UK became the first major economy to publish an Industrial Decarbonisation Strategy. The long term ambition is to reduce sector emissions by at least 90% by 2050 compared to 2018 levels.

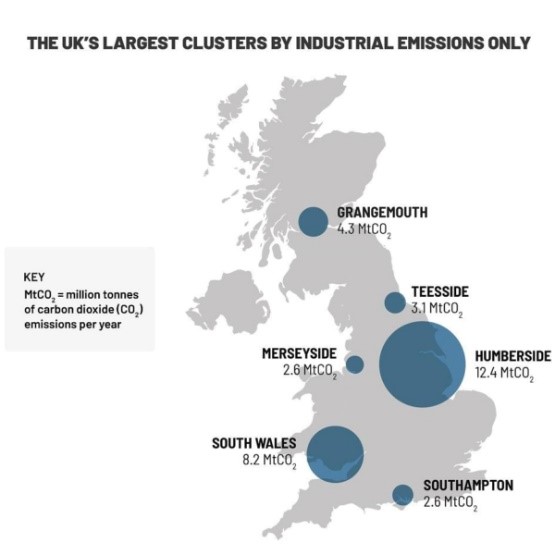

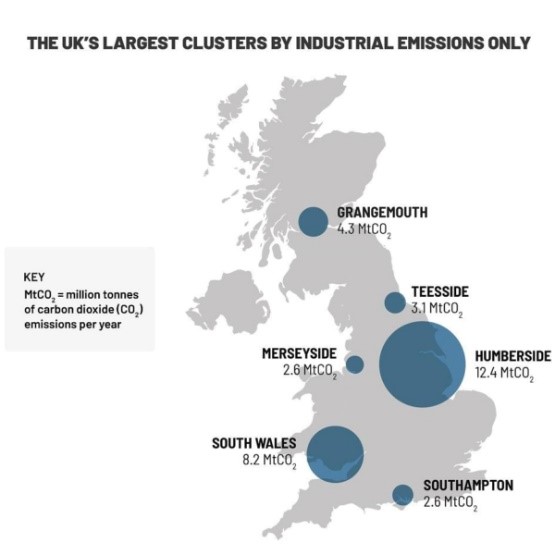

The midterm strategy is more geographically specific. Just over half of UK industrial emissions arise from six coastal industrial clusters. The government plans to deliver at least one low-carbon industrial cluster by 2030 and one net zero carbon industrial cluster by 2040 through the deployment and scale up of CCS and low carbon hydrogen. In Oct 2021, the East Coast (combining Humberside and Teesside) and HyNet (Merseyside) clusters were selected as pilot sites for this work.

Location and emissions of UK largest industrial clusters by CO2 emissions (Industrial Decarbonisation Strategy p.119)

Prioritising the deployment of decarbonisation infrastructure into clusters is not, in itself, controversial. Infrastructure is expensive. So, too, is research and development. Clusters have the guaranteed customer base, institutional capacity and economies of scale needed to bring new technologies to maturity. Their coastal location provides easy access to offshore wind and transport links for future trade in hydrogen and carbon. Many coastal communities are also “left behind” communities, specifically because of their distance from other centres of population and their industrial heritage.

Investment here supports government commitments to use industrial decarbonisation to level up the economy. But the approach does not deliver equally for all places. While the lessons learned from the pilot sites may transfer easily to the remaining clusters, the benefits for sites outside clusters — the dispersed sites which generate the remaining 47% of industrial emissions — are less clear.

The strategy here is for firms to apply for government grants to improve energy and material efficiency, followed by electrification when grid upgrades are complete. This means that industries in inland locations like Sheffield, Bradford, the Black Country — the industrial heartlands of the UK — have fewer options to decarbonise than their cluster-based competitors.

The issue is exacerbated by a lack of clarity about the timetable for electrification. Facing questions about the long-term viability of these sites, there is a risk firms invest in other, lower risk, facilities either in clusters or abroad. The resulting two-tier system threatens not only decarbonisation targets but may worsen longstanding regional inequalities.

Can locally-led initiatives address this emerging issue? Potentially, but being the first major economy to develop an industrial decarbonisation strategy means there are few examples to guide us. Local authorities have an acknowledged role to play in delivering action on climate goals, but their powers focus on waste, transport and social housing with little influence over industrial emissions.

The 2017 Industrial Strategy White Paper attempted to address the shortfall by introducing Local Industrial Strategies. These, however, were axed from the Treasury’s 2021 Plan for Growth, which contains no regional or local element, leaving the Select Committee for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy to conclude:

It is unclear what structure can now underpin strategic conversations about industrial policy at the local level, and support focused engagement between local areas and national Government[1]

This limits local influence on industrial decarbonisation to indirect routes. One key area is skills. A lack of adequate skills and training presents a major challenge for the implementation of industrial decarbonisation strategies and local authorities will play an important role in supporting the workforce to reskill. But we know decarbonising energy-intensive industries also requires support for infrastructure and innovation. What role can local initiatives play here?

In theory, Local Area Energy Plans (LAEPs) could inform conversations about infrastructure. The process of developing a LAEP is intended to help local stakeholders, utilities and infrastructure owners in understanding what the low carbon transition means for the energy profile of their area, including the infrastructure required to enable it. However, the solution is not a complete one. Not all aspects of industrial energy use are included and piecemeal funding means not every place is developing one. Most significantly from the perspective of delivering local action, the process is purely advisory. LAEPs are intended as a tool to guide conversations about local priorities, not a mechanism to access funding to implement them.

Innovative sector-led initiatives facilitated by local support provide another part of the answer. One example is “Glass Futures”, a research technology organisation which, in partnership with local authorities, is developing a pilot plant for decarbonised glassmaking on the site of a former glass works in St Helens, Merseyside. Once operational, the facility will provide a global Centre of Excellence for firms to undertake research into glass decarbonisation.

Such initiatives demonstrate how energy-intensive industries might cooperate yet still maintain competitive advantage while addressing climate change. However, experience shows that the success of such initiatives is often reliant on key individuals or groups with the experience, determination and networks to galvanise change. In short, it relies on local capacity.

And this is the crux of the matter. If decarbonising dispersed industrial sites is to rely on local people and institutions being proactive, bidding for funding, building partnerships, developing plans, then not all places will decarbonise at the same rate. Those that do so will be well-situated to attract further investment into their area. Those that don’t are likely to fall further behind.

These places also need support if we are to deliver a Just Transition. Industrial materials are a major contributor to industrial emissions, but they also provide the means to abate them. We need an industrial decarbonisation strategy that actively supports local areas to decarbonise their dispersed industries, rather than relying on local capacity to deliver. Otherwise rather than levelling up the country, industrial decarbonisation risks hollowing it out.

This article was first published as a Commentary for the Place-based Climate Action Network (PCAN).

About the authors:

Dr Imogen Rattle is a UKERC funded Research Fellow in Local Low Carbon Industrial Strategy within the Sustainability Research Institute at the University of Leeds. Dr Alice Owen is a Professor at the Sustainability Research Institute at the University of Leeds and leads the business theme for the Place-based Climate Action Network (PCAN)

[1] Business Energy and Industrial Strategy Committee, Post-pandemic economic growth: Industrial policy in the UK. 2021, House of Commons, Available from : https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/6452/documents/70401/default/