The war in Ukraine has completely upended the EU’s views on energy security. The bloc now aims to get rid of Russian fossil fuels “as soon as possible.” This will likely be hardest for natural gas. In 2021, Russian gas accounted for approximately 45% of total imports and close to 40% of total consumption. Some EU members, such as Italy and Germany are heavily reliant on Russian gas and, quite understandably, have been hesitant to support an EU-wide embargo with immediate effect.

Yet, according to the European Commission’s REPowerEU plan, launched in March 2022, gas imports from Russia must be reduced by two-thirds before the end of 2022. At the same time, EU gas storage infrastructures need to be filled up to at least 80% of their capacity by November 2022, rising to 90% for the following years. This means significantly reducing demand for gas while simultaneously increasing non-Russian gas supply.

The EU is particularly looking to boost import from Liquified Natural Gas (LNG). Contrary to pipeline gas, which has geographical limitations, LNG can be shipped and imported from many places in the world. Until very recently, Europe had a different role in the global LNG market. As most of its gas was imported through pipelines from Russia, Norway or Algeria, its reliance on the global LNG market was relatively limited. Large Asian economies were the main marginal buyers of LNG, while Europe mostly acted as a ‘sink’ whenever there was an oversupply. Competition among these import-dependent regions was therefore restricted.

Two months into the war, and with alternative pipeline imports from Norway and Algeria at full capacity, this dynamic is fundamentally changing. The EU has become a direct competitor for LNG with other markets in Asia and Latin America, as it is willing to snatch LNG cargoes on the spot market at almost any price. In the period 2019-2021, on average 27% of US LNG exports went to the EU. By January 2022, even before the war, this had already shot up to 37%, mainly driven by the premium in European prices, aided by lower gas demand in Asia due to a mild winter and lower levels of economic activity in China due to continuing Covid lockdowns.

Figure 1. European and Asian monthly LNG imports (2022 vs. previous 5 years). Source: Timera Energy

Often overlooked, however, Europe’s scramble for energy comes at the expense of others. It is already prompting energy crises in developing countries as they cannot compete with them for LNG shipments. Secondary consequences, such as food shortages, inflation, or blows to the fragile recovery from the Covid-19 pandemic could then easily spill-over into political turmoil.

In the current global energy zero-sum game, one country’s quest for energy security, creates another’s insecurity.

Particularly vulnerable countries are those that, in recent years, have sought to increase their dependence on LNG in an attempt to offset the need for imports of fuel oil and coal. These include, amongst others, Asian developing economies the likes of Sri Lanka, Pakistan and Bangladesh.

To offset potential political instability and buffer the cost increases for households and factories, some of these governments initially resorted to fossil fuel subsidies. But the associated financial burden quickly became too much to bear, and they started to look for a way out. In Pakistan and Sri Lanka people have been taking to the streets to protest the cost-of-living crisis. In Pakistan, it contributed to the ousting of Prime Minister Imran Khan, while Sri Lankan President Rajapaksa dissolved his cabinet and appointed a new one. Importantly, however, high energy prices certainly are not the only reason for the public’s dissatisfaction with its political leaders.

Pakistan is cutting electricity to households and industry, while simultaneously turning to cheaper but more polluting alternatives to LNG, namely coal from Afghanistan. Already the fifth-most populous in the world, Pakistan is also home to some of its most polluted cities. A switch to coal will only further aggravate environmental and health problems. It is now reportedly looking to file for damages on European LNG traders’ defaults on long-term supply contracts.

Halfway across the globe, others are feeling the energy crunch as well. Despite being home to some of the largest (shale) gas reserves in the world, Argentina’s gas industry has been suffering from chronic underinvestment that has left the it unable to meet domestic demand, let alone providing global markets. At the start of the winter in the southern hemisphere, it must now enter the LNG arena and compete with the EU member states seeking to replenish their storage facilities.

In the longer term, it casts further doubt on the ability and political will of cash-strapped developing and emerging economies to finance a much-needed energy transition to combat climate change. Even before the pandemic and the war, there was already a big investment gap to finance clean energy transitions in developing and emerging market economies.

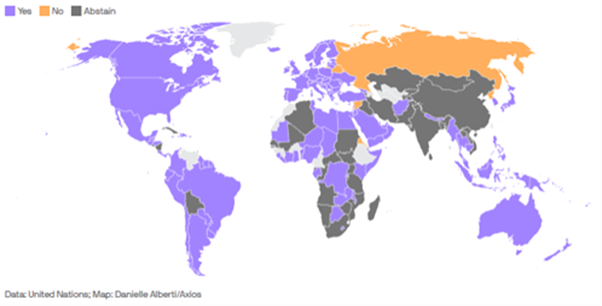

Perhaps unsurprisingly then, the (developing) world is not as united against Russia as the West would like it to be. Russia’s fellow BRICS countries—notably China, India and South Africa—abstained from the UN General Assembly vote on 2 March that demanded that Russia withdrew from Ukraine. In Latin America, Brazil and Mexico are not participating in the West’s sanction regime.

Figure 2. How countries voted on UN resolution of 2 March. Source: Axios.com

The Indian government has shrugged off Western criticism of its purchase of Russian crude oil at a discount in an attempt to secure “good deals” amid global market volatility. In yet another example of the growing division between the West and Rest, OPEC+, has so far declined to ramp up production to make up for (potential) Russian output losses. Much to the West’s chagrin. Saudi Arabia and the UAE, traditional US allies and the only two OPEC members that have significant spare capacity, will only increase production when it is in their own financial interest. Instead, the US has had to release a record-breaking 180 million barrels of oil from its own strategic reserve.

In the end, the EU and its partners risk further alienating non-Western countries with this sanction regime. Particularly as it is inflicting secondary economic pains that it has so far been unwilling to acknowledge, let alone address. The EU should be aware of the long-term risks this could create or aggravate: from a division between ‘the West and the Rest’ that is crystallising and may lead to geopolitical re-alignment with Russia and China for many developing countries, to the climate impacts of a postponed energy transition as the window to limit global warming to 1.5°C is rapidly closing.

To avoid this, the EU should be clear about its long-term strategic objectives. Is it about getting rid of Russian fossil fuels, only to lock in US LNG, Saudi oil, or German coal? Or is it about accelerating a fossil fuel phase-out and energy transition as a whole? Only the second option leaves the opportunity for the EU to act as a responsible climate leader that supports developing countries to prepare for the energy transition at an equitable pace.

Suggested Further Reading—

This article was translated and updated for the Geography Directions website, from an earlier version that first appeared on the website of Mo* Magazine (in Dutch).