In this blog, Magnus Jamieson reflects on the growth of data centres and their impact on the electricity system and water resources.

There is an enormous amount of money relying on the success of AI and generative AI-driven economic growth. OpenAI alone has commitments of $1.4 trillion (1), or approximately 10% of the entire USA’s retail sector sales projections for 2028 (2). It is incumbent on power system planners and operators to make sure that the power system of today and the future is able to adapt to changes in society. They must ensure power is affordable for customers and that it is clean and sustainable for future generations. At a time when societies are asking citizens to cut their emissions, the data-driven economy is demonstrating ferocious hunger for silicon and electricity. To what degree should we be concerned? A recent workshop at Imperial College London (3) sought to investigate, primarily, the power system issues surrounding data centres, which I attended. A broad range of speakers from industry and academia provided a healthy amount of discussion on these matters of technical substance, but there is more to the data-driven revolution than engineering challenges.

In Great Britain, much of our data centre capacity is concentrated in the southeast of England, within and surrounding Greater London. Slightly over 60% of GB’s data centres reside in this area (4). This is primarily driven by large companies such as Amazon, Google and Microsoft with a need to keep latency low and be close to the UK’s economic centre, though data centres are diverse in form and function (5).

Data centres need several things to operate: a reliable and high-quality power supply, meaning that the voltage is within a guaranteed, narrow range; expertise to build, operate, and maintain them; depending on their cooling technology, an amenable climate and adequate water supplies; and robust connectivity to the telecommunications infrastructure of the country in which they are built.

Data centres in the UK can generally be categorised into four groups, according to the House of Commons Library (6): enterprise (owned and operated by a single organisation for internal use); co-location data centres (owned by a third party and rented to users); hyperscale (larger facilities built by major data providers and users such as, as previously mentioned, Amazon, Microsoft, and Google); and AI data centres specialised for high-performance computer needs of, for example, Large Language Models (LLMs). In practice, data centres can be used for a wide range of purposes in the digital economy, from data backups, high complexity economic modelling, and transaction processing from the banking sector to real-time conversation processing of the kind used by LLMs such as ChatGPT. Data centres may also be used for purposes such as cryptocurrency mining or image processing for generative AI tools.

Ireland has seen rapid growth in data centre demand usage as a result of investment from companies like Google. There, data centre electricity demand has grown to approximately 20% of the country’s annual total and could be as much as 28% by 2031. EirGrid has suspended applications for new data centres in Dublin (7), reflecting what has been called an “effective moratorium” on data centre development in Ireland more generally (8). Denmark is projected to see its demand from data centres grow sixfold to approximately 15% of electricity demand by 2030. Globally, demand by data centres for electricity is growing by 20-40% annually. In 2022, 110 TWh were used solely for cryptocurrency mining (9). For context, the total electricity demand in the UK in 2023 was 316.8 TWh (10).

A driver for the rapid growth of data centre demand is that the tasks being carried out can require much more energy per request than something that used to be done without the use of AI, particularly online searches. For example, there is nearly 30× more energy consumed in processing an AI-powered Google search compared to that of a standard search (11). When used to find information, generative AI tools such as ChatGPT are designed to be more interactive than traditional search engines, which fundamentally changes the interactions between the user and the service, and the amount of energy a user consumes in the process of carrying out daily activities.

Even if the actual process of performing an AI search was made more computationally and energy efficient, this would not necessarily result in any reduction of the demand from the data centres processing these requests. Instead, what would likely happen is that providers would use the enhanced capacity to increase throughput, thus profit, due to a phenomenon in economics called Jevons’ Paradox or, more specifically in the context of the energy system, the Energy Rebound or Rebound Energy. Rebound Energy can be understood as “the phenomenon where improvements in energy efficiency lead to an increase in energy consumption, resulting in actual energy savings being lower than expected.” (12) Thus, this would not actually result in a net reduction of energy demand, rather, the energy and chipsets would be used to process a larger set of data or perform more tasks instead. Users would effectively get a better-quality product rather than paying a reduced service fee thanks to energy savings. If a data centre saves lots of money through efficiency gains in cooling, they will simply use the saved money on energy for computation. This became a particular subject of discussion when DeepSeek emerged as a far more efficient genAI model than legacy ChatGPT models (13), with Peter Howson of Northumbria University calling it AI’s “Sputnik moment” (14) in that “the emergence of a more efficient rival caused America to allocate more resources to the space race, not less.”

As large loads, data centres also present challenges to the operation of power systems for a wide range of reasons. Their tendency to cluster near urban centres could add further strain to already congested systems. There is also a lack of standards in terms of how data centres should respond to system perturbations. These could be, for example, instabilities in voltage levels or system frequency caused by fluctuations in power imbalance on the system. Data centres want a consistent, high-quality infeed of power and so will tend to have significant redundancy, such as uninterruptible power supplies (UPS), battery storage and their own, on-site backup generation. For example, following the North Hyde Substation outage in March 2025, Heathrow airport and thousands of homes and businesses lost power, the three local data centres that lost mains supply were able to continue operations through their own backup generation (15).

Power network faults could see gigawatts of demand disconnect from the network. The ‘step change’ in demand could potentially cause or exacerbate system operability challenges, both when they disconnect from the system (causing rises in system voltage and frequency) and when they reconnect (causing possibly damaging swings in the other direction). One such event occurred in Virginia, USA in July 2024 when a fault on a 230 kV line resulted in the disconnection of 1.5 GW of data centre demand (16). While system operators are accustomed to planning for large losses of ‘infeed’ – generation or imports via interconnectors – and to managing the resulting system frequency and voltage falls, such large, instantaneous losses of ‘outfeed’ are a relatively new phenomenon. As the system collapse in Spain and Portugal in April 2025 reminds us (17), voltages that are too high can be just as much of a problem as voltages that are too low. The same thing applies to frequency. This may lead to a need for system operators to spell out and enforce requirements for large loads to be able to ‘ride through’ network faults in a way that is similar for generators.

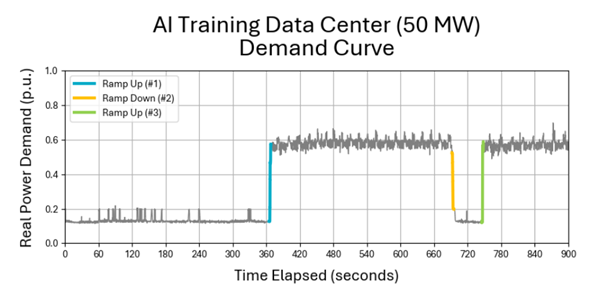

Even in the absence of network faults, data centres can demonstrate significant swings in demand over short periods, for example, between nominal operations and ’training’. ‘Training’ in an AI context refers to “the process of feeding curated data to selected algorithms to help the system refine itself to produce accurate responses to queries” (18). Figure 1, taken from a report from the North American Electric Reliability Corporation in the United States (NERC) (19), illustrates the types of swings possible in an AI Training Data Centre. The data centre in question has a peak power demand of only 50 MW. In Britain, we have already seen connections of data centres which are likely to reach 150 MW of capacity (20), and there are potential new connections under construction as large as 720 MW (21) . If many megawatts of data centre demand are located near each other and can’t ride through a fault, the simultaneous loss of demand, as seen by the rest of the power system, could be huge. In normal operation, although some diversity in their behaviour on second-by-second timescales might be expected, they could add up to very large, fast and repeated swings in total demand that need to be balanced by enough very flexible electricity production or energy storage.

Figure 1 – Representative demand profile of an AI training data centre. (Source: NERC)

There is also the issue of how these data centres use water. Water can be used in a closed cycle for cooling for long periods of time (22). However, for high intensity cooling demands a data centre may utilise evaporative cooling (as opposed to immersion or air cooling). In a warming world with increasingly strained surface freshwater and groundwater supplies, particularly in regions where shale gas extraction may already be rendering water supplies precarious, extracting water in this manner could push regions into water shortages with consequences far beyond those we can anticipate. Compounding this, many data centres, especially in the US, are building their own generation. Often it is a fossil fuelled thermal plant and is a source of significant controversy, for example, at xAI’s Colossus data centre in Tennessee (23). Furthermore, thermal electricity generation itself consumes water. The electricity efficiency gains of evaporative cooling must be balanced against the localised water consumption and stresses wherever these data centres are constructed.

When such enormous amounts of energy are being directed towards the processing of cryptocurrency and image generation, we must eventually, as a society, take a step back and examine what it is we’re actually looking to do with these technologies. AI and machine learning have tremendous potential in the fields of medicine and engineering, where they can address tightly defined, well-understood problems that would benefit from large-scale, intelligently-targeted processing. However, the typical life-cycle for graphics cards of the kind used for these tasks is only around 5 years. These data centres will require a relatively continuous supply of chipsets just as much as they will electricity, water and staff. It is also difficult to know whether these replacements of chipsets would be an ongoing, Ship of Theseus style maintenance process, or overhauls and wholesale replacement of racks as they age. The sustainability and longevity of large-scale data centres reliant on these technologies is therefore unclear. This is a matter of ongoing research for manufacturers, as the rate of failure of chipsets will directly affect not only the operating expense of data centres, but also the longevity, profitability and viability of data centres – and the income streams to manufacturers who build, replace and maintain these chipsets (24).

There is an enormous amount of wealth and, increasingly, physical capital dependent on the success of these technologies – but it still isn’t clear what we are actually expecting them to do for us. If we replace call centres with AI chatbots, what happens to the service sector? If we replace low-effort, low-stakes media generation with generative AI, what happens to sectors of the economy which rely on human creativity and ingenuity that genAI can superficially replicate? What does a society where increasing amounts of our cultural world are artificially generated look like? More relevantly for those of us who do research in and around energy, what does the power system which actually facilitates that world look like? What happens if the expected returns simply don’t materialise and we, as a society, have built a bunch of data centres and infrastructure to support a mirage? Who pays for it if it all goes wrong? These are the questions we, collectively, must answer in the coming years – and not all of the answers will be comforting.

Magnus Jamieson is a post-doctoral Research Associate in the Department of Electronic and Electrical Engineering at the University of Strathclyde who has contributed to the UKERC research theme of Delivering Energy Infrastructure.